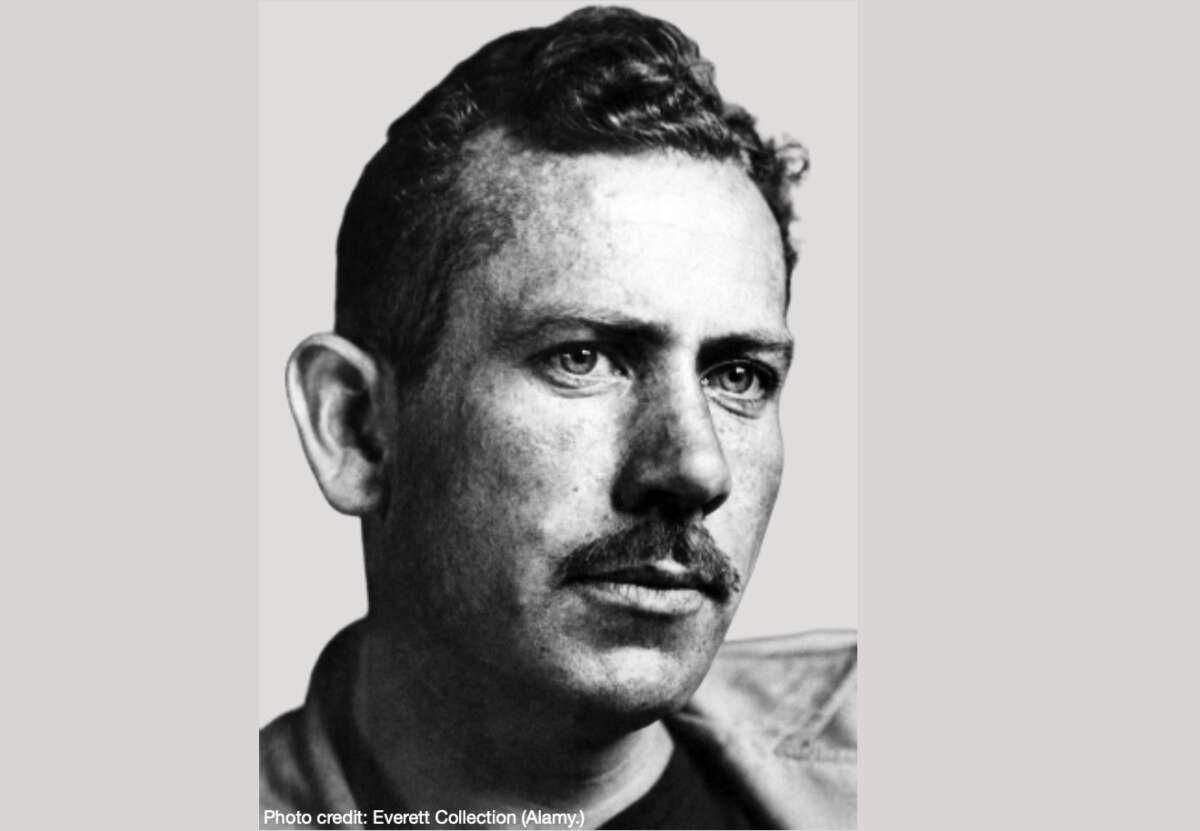

One of the three “giants” who influenced my life was John Steinbeck. I was introduced to him in high school when we were assigned to read “Of Mice and Men,” but I was bitten by the bug and hungrily read every book he wrote (including “Travels with Charley: In Search of America“) over the next two years. Every book, that is, but one.

Somehow, his work “The Log from the Sea of Cortez” slipped through the cracks. But before I go any further, let me explain what John Steinbeck means to me.

First of all, I love his writing style. In “The Wayward Bus,” he might spend three pages talking about a fly on a piece of stale cake in an equally wayward diner, and it would be positively riveting to me in the way he described it.

If you ask me why I like Steinbeck one the one hand but don’t like Hemingway, for example, on the other, I might say “Hemingway was a drunk.” But then, so was Steinbeck. I guess I just never connected with Hemingway, having only read “The Old Man and the Sea.”

The main effect that Steinbeck had on me was in shaping my liberal idealism. Who could read “Grapes of Wrath” or “In Dubious Battle” and not shed a tear or root for the downtrodden? Years later, I would teach macro and microeconomics to college students, and I would point out that there was a prize that society pays in human misery as capitalism—for all its merits—destroys dreams, ambitions, even entire civilizations, and I refer to the Mayans, Aztecs, Iroquois and others as examples.

And there was always some deep, metaphysical dimension in many of Steinbeck’s writings, such as in “To a God Unknown.” The protagonist lives in a land where it has ceased to rain. Before moving away, the inhabitants tried everything to open the heavens. On the last pages of the novel, the central character concludes that he is the rain, and he opens his wrists as an offering to life, itself, sacrificing himself in the process. He feels the first drops of a cloudburst just as he loses consciousness.

THE DOGS OF WAR

Like most of us, I have been concerned by the recent news. The only events more dismal than domestic news is the international news. As if the Presidential election were not riveting and foreboding by itself, there are the prospects of war. The drum beats constantly and even at night it fills one’s dream. I’m not as concerned about the Mideast as I am about eastern Europe. Of late, Russia has imported thousands of North Korean shock troops and soldiers from another continent to brutalize and terrorize the people of Ukraine. South Korea is expected to send their weapons to Ukraine to fight their neighbor on the north in another part of the world. And what will follow if Ukraine, using U.S. advanced munitions, kills hundreds or thousands of North Koreans in the cause of Ukranian self-defense? Russia is continuing to threaten NATO and the U.S. with World War III while holding scheduled and impromptu nuclear drills. What more can they do now, except actually cross that threshold?

ARE CIVILIZATIONS DESTINED FOR DESTRUCTION?

In an answer to the Fermi Paradox which wonders where any interstellar life is, if it exists at all, one theory is that a civilization will eventually destroy itself (or be destroyed by another) before it is capable of contacting us. The current “Dark Forest” hypothesis warns us about broadcasting our existence to other stars, lest we be destroyed as other civilizations were in our past. Is our fate written in the stars as well?

NOW TO THE LOG . . .

In his six-week voyage around the Sea of Cortez (another, perhaps more charming name for the Gulf of California), Steinbeck travels with a naturalist (Ed Ricketts) who appears in other books by Steinbeck such as “Cannery Row,” “Tortilla Flat” and “Sweet Thursdays.” The voyage is designed to be a scientific expedition that mixes work with play, or at least, with bourbon. Ricketts is interested in cataloging the creatures of the sea that they encounter along the way in that unique, aquatic ecosystem. Sometimes, the marine life is found in shallow, tidal pools while other times it frequents the deeper waters. No matter. Steinbeck writes about people and places they see as well as what they scoop up in their nets.

The year was 1951. World War II had just ended and the Korean Way had just started. No doubt, this weighed heavily on Steinbecks mind. Here is a passage from his “Log . . .”

“We have looked into the tide pools and seen the little animals feeding and reproducing and killing for food. We name them, and describe them and, out of long watching arrive at some conclusion about their habits so that we say, ‘This species typically does thus and so,’ but we do not objectively observe our own species as a species although we know the individuals fairly well. When it seems that men may be kinder to men, that wars may not come again, we completely ignore the record of our species. If we used the same smug observation on ourselves that we do on hermit crabs, we would be forced to say, with the information at hand ‘It is one diagnostic trait of Homo sapiens that groups of individuals are periodically infected with a feverish nervousness, which causes the individual to turn on and destroy, not only his own kind, but the works of his own kind. It is not known whether this be caused by a virus, some airborne spore, or whether it be a species reaction to some meteorological stimulus as yet undetermined.’ Hope, which is another species diagnostic trait–the hope that this may not always be—does not in the least change the observable past and present. When two crayfish meet, they usually fight. One would say that perhaps they might not at a future time, but without some mutation, it is not likely that they will lose this trait. And perhaps our species is not likely to war without some psychic mutation which at present, at least, does not seem imminent. And if one place[s] the blame for killing and destroying on economic insecurity, on inequality on injustice, he is simply stating the proposition in another way. We have what we are. Perhaps the crayfish feels the itch of jealousy, or perhaps he is sexually insecure. The effect is that he fights. When in the world there shall come twenty, thirty, fifty years without evidence of our murder trait under whatever system of justice or economic security, then we may have a contrasting habit pattern to examine. So far there’s no such situation. So far, the murder of our species is regular and observable as our various sexual habits.” (pp. 15-16.)

I saw something the other day and just glanced at it, not knowing for sure whether it was someone’s fanciful notion or rather a scientific poll. So, take it with a grain of salt. The question which was said to have been posed in the survey was “What is the first thing that crosses your mind when you meet someone interesting of the opposite sex while trolling online?” Men were said to have reported “Is she good looking?” I can believe that. Women were said to have responded “Will this guy hurt me?” I can also believe that. Maybe, Steinbeck could have believed that himself. He had a checkered past with women that was not mentioned when he received his Nobel Prize for literature. Nor did he mention his wife once in the “The Log of the Sea of Cortez,” and she was the only passenger on board.

Tensions in people must be relieved. Some people relieve them through their normal ego defense mechanisms (e.g., “My professor failed me in history.”) Others, use harmless escapes such as going to the movies, helping themselves to a pedicure or a second serving of comfort food, sex and so on. Some people, however, are more destructive when it comes to relieving stress. They drink to excess or do recreational drugs. They can only relieve tension by smashing something (anything.) They drive recklessly to “take out their anger” behind the wheel of their car. They set fires, molest children, kill prostitutes or vagrants and so on. At that point, their stress lifts temporarily, only to start once again and the search for the next victim begins.

I spent a year at war dodging missiles and mortars. You could not see the enemy from 20,000 feet in the air during the day or from 200 feet away at night on the ground. But perhaps the most vicious war I ever heard of was the Bosnian War. It ran from April 1992 until December 1995, starting as the firm grip of communism started to crumble. The Balkan Republics began to break away from Yugoslavia. The war also had a religious dimension. Bosnia was predominantly Muslim while Serbia was Orthodox Christian. Until the war began, Muslims and Christians lived in peace. They exchanged gifts one with another as the celebrated birthdays. They cared for each other’s children. The supped together, made love to each other, laughed and cried together. But then suddenly they turned on each other. Love turned to hate overnight. They did not just stab and shoot each other. They mutilated each other’s bodies in the aftermath.

WHEN DREAMS TURN INTO NIGHTMARES

Two individuals, Admira Ismić a Bosnian Muslim young woman and Boško Brkić, a Christian Serb from Herzegovina, both 25 years of age and madly in love, decided to get the heck out of Dodge. They looked all American, like Danny Zuko and Sandy Olsson on the posters for the movie “Grease.” On May 19, 1993 they made their escape. Holding hands, they carefully approached and started crossing the Vrbanja bridge to freedom. From a distance, a Serbian sniper matter-of-factly shot Boško who was a short way from Admira. As Boško cried out helplessly, dying, Admira ran to help her high school sweetheart before being shot, herself. She crawled to him before being shot one again and she never quite reached him. These star-crossed lovers, known as the “Romeo and Juliet of Sarajevo,” were dead. And with them died the hopes for peace and reconciliation between two peoples for the near future. The heartless sniper remains at large as far as is known.

Why can we not rise above crustaceans in our relationships with each other? A hermit crab has 254 chromosomes while we only have 46, but that is not a valid comparison. When a human has an additional chromosome (as with Klinefelter’s Syndrome or Down’s Syndrome), the result can be devastating. Still, hermit crabs are considered to be highly intelligent (among their own kind, that is.) They perceive pain, choose from a selection of shells that one that best approximates their needs. They can plan ahead, and they can use makeshift tools. But as Steinbeck discovered, they compete aggressively over territory, resources and females, just like Homo Sapiens are. Is this what we are reduced to? Does cogito ergo sum mean anything to a crab? To us? Does a crab understand Descartes and the philosopher’s desire to search for truth? Do we?

Many liberals committed suicide during and after World War I. Products of the Enlightenment, they could not fathom how rational, intelligent, modern men and women could fight to the death using lethal weapons and poison gas. And yet they did. Today, long after dreams of a “peace dividend” on which to balance our national budgets, Western democracies are once again inching towards a war footing to match that of Russia and China.

Somehow, we must learn individually and collectively to rise above our breeding, to become more than just the sum of our parts. The Admira Ismićs and Boško Brkićs of the world need a future, a hope and a life.