PORTIA: “The quality of mercy is not strained:

it drops on to the world as the gentle rain does – from heaven.

It’s doubly blessed. It blesses both the giver and the receiver.

It’s most powerful when granted by those who hold power over others

It’s more important to a monarch than his crown.

His sceptre shows the level of his temporal power –

The symbol of awe and majesty in which lies the source of the dread

and fear that kings command.

But mercy is above that sceptered power.

It’s enthroned in the hearts of kings.

It is an attribute of God himself.

And earthly power most closely resembles God’s power

when justice is guided by mercy.

Therefore Jew, although justice is your aim, think about this:

none of us would be saved if we depended on justice alone.

We pray for mercy and, in seeking it ourselves, we learn to be merciful. I’ve spoken about this to soften the justice of your plea.

If you insist on pure justice, however, then this serious Venetian court

has no alternative other than to pronounce sentence against the merchant there.”

– William Shakespeare, Merchant of Venice, Act IV, Scene I.

In this monologue addressed to Shylock the Jew, Portia tells Shylock and us that mercy is something from God, a gift of unmerited grace, and that a monarch who can understand this and who tempers justice with mercy is indeed a wise, Godly person. Portia also says to pray for and to seek mercy, because in doing that, we, ourselves, find mercy which is a good thing, for without mercy, “none of us would be saved.”

The symbolic meaning of rain in Scripture

The use of rain is a powerful metaphor in Scripture. In Deuteronomy 32:2 God says: “My doctrine shall drop as the rain, my speech shall distil as the dew; as the small rain upon the tender grass, and as the showers upon the herb.” Hosea 10:12 promises that God will come and shower His righteousness on His people.” Rain is also symbolic of the Holy Spirit.

But let’s look more closely at mercy, and the quality or nature of mercy.

A tupology

Catholics actually have a typology as it applies to mercy: corporal works of mercy and spiritual work of mercy. As long as we don’t confuse grace with works, the Catholic model is a convenient guide for our purposes. Catholic theologian Thomas Aquinas writing in Summa Theologica II-II Q30;A4 notes: “It is clear that almsgiving is, properly speaking, an act of mercy. This appears in its very name, for in Greek (eleemosyne) it is derived from having mercy (eleein.). Thus, the first four items on the list of corporal works of mercy involve almsgiving.

Corporal works of mercy

Corporal works of mercy are those that tend to the bodily needs of other creatures. The standard list is given by Jesus in Chapter 25 of the Gospel of Matthew, in the famous sermon on the Last Judgment. They are also mentioned in the Book of Isaiah.[13] The seventh work of mercy comes from the Book of Tobit[14] and from the mitzvah of burial,[15] although it was not added to the list until the Middle Ages.[16]

The works include:

- To feed the hungry.

- To give water to the thirsty.

- To clothe the naked.

- To shelter the homeless.

- To visit the sick.

- To visit the imprisoned, or ransom the captive.

- To bury the dead (from the apocryphal book of Tobit 1:16-18)

The spiritual works of mercy are:

- To instruct the ignorant;

- To counsel the doubtful;

- To admonish sinners;

- To bear wrongs patiently;

- To forgive offences willingly;

- To comfort the afflicted;

- To pray for the living and the dead.

Prayers for the dead

As far as the spiritual works of mercy are concerned, not everyone is capable of instructing unlearned people in the Gospel, or perhaps counseling Christians whose faith is weak. But they can learn to bear wrongs with patience, to forgive others, to offer words of comfort, and to pray. Protestants tend not to pray for the dead, though I do personally. Perpetua believed that her prayers helped her late brother. Prayers for the dead are not mentioned in the Bible that Protestants use, but they can be found in 2 Maccabees, 12:38-46. 1 and 2 Maccabees are books of a group of works called the apocrypha which appear in the Catholic Bible. When Martin Luther translated the Bible from Latin into German, he wasn’t sure where to insert the books of the apocrypha which were scattered among the Old Testament books, so he collected them and stuck them at the end of the Old Testament. Since the apocrypha is largely literature, personal accounts and history, with some prophecy, but with nothing that adds to or takes away from what the other works of Scripture teach, the books of the apocrypha were never considered by many Protestants to be inspired to the same extent as the rest of the Bible, though the early church councils did, and some liturgical Protestant denominations such as Anglicans and some Lutherans do include the apocryphal books in their Bible. Eventually they were removed. Luther was asked if it was permitted for his followers to pray for the dead like they did when they were still Catholic, and while Luther did not forbid his followers to do so, neither did he think it made much difference as far as the dead are concerned. Luther believed the dead would be judged on whether they had come to Christ while in this life, and if not, then nothing could be done now to save them, and if so, then they were assured of a place in heaven anyway.

For most of my life, I thought that mercy was a transaction between two people or more, where the grantor of mercy has a superior position than the grantee. For example, God who is our Sovereign freely grants mercy on Judgment Day to his subjects. Or a police officer who pulls a person who was speeding off the road but elects to give him a warning instead of a ticket. Or, a judge sentences a defendant to a more lenient sentence than the defendant might otherwise expect or merit. As a teacher, I am never short of opportunities to be merciful to failing or marginal students who petition me to provide them a “bump” to the next higher letter grade, or allow them to submit late work, extra credit and so forth. How could the reverse be true? How could a bank robber show mercy to a judge, or a traffic offender show mercy to a police officer (unless they were taken hostage?).

Priam asks Achilles for Hector’s body

I am reminded of how Achilles, the Greek warrior and de facto leader of the Greeks in Homer’s Iliad showed mercy to King Priam of Troy and allowed him to retrieve the body of his son Prince Hector who Achilles had slain. Achille’s cousin Patroclus was slain by Hector earlier, and Achilles killed Hector in revenge. Achilles had no obligation to treat Hector with deference or respect, nor to return him to the Trojans. Yet, a father’s tears and mournful request convinced Achilles to be merciful to Priam. Said Priam:

“Think of thy father, and this helpless face behold

See him in me, as helpless and as old!

Though not so wretched: there he yields to me,

The first of men in sovereign misery!

Thus forced to kneel, thus groveling to embrace

The scourge and ruin of my realm and race;

Suppliant my children’s murderer to implore,

And kiss those hands yet reeking with their gore!

– “Iliad,” Book XXIV

This is passage above between Priam and Achilles is an example of the mercy to bury the dead.

“It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done. . .”

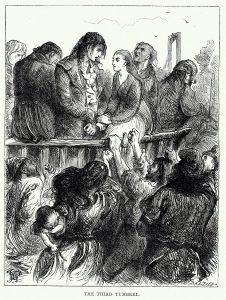

My favorite example of benevolence comes from Charles Dicken’s “Tale of Two Cities,” which is set in the French Revolution. Charles Darnay is an aristocrat who is represented by an attorney named Sydney Carton in a legal affair. Carton and Darnay coincidentally bear a striking resemblance to each other, and each compete for the affection of a young woman named Lucie Manette. Lucie, with deep feelings for Sydney, nevertheless chooses Charles to be her spouse to the sadness of Sydney. While in France, Darnay is arrested for the crimes of his father and his uncle and is sentenced to death. However, putting Manette’s happiness and that of Darnay’s as well before his own, Carton visits Darnay only hours before the execution. He drugs Darnay who loses consciousness and exchanges clothes with him, presenting himself to the jailers when they come for Darnay. The jailers remove the unconscious man from the jail thinking the man is Carton and Darnay is rescued. Carton, meanwhile is unceremoniously loaded in the tumbril with other prisoners on the way to the guillotine. Carton has been musing on the Bible verse where Jesus says: I am the resurrection and the life . . .” As Carton steps out of the cart onto the scaffold, he thinks: “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.”

Sydney Carton’s motive

Many commentators believe that Carton saw his substitutionary death as a means to receive access to Heaven. In at least one sense, it was the substitutionary death of Christ that opened the doors of Heaven to us if we believe. John quotes (15:13) Jesus as saying: “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends, which is precisely what Carton did. But was what Carton did, an act of mercy? Catholic historians would point to the creation of religious orders through the middle ages that were formed to visit the imprisoned, or ransom the captive. Carton, in the capacity of Darnay’s lawyer, visited him in prison regularly to plan Darnay’s defense and appeal. And at the cost of his own life, Carton ransomed the prisoner Darnay.

We’ve all gone astray

For much of this generation, television preachers in particular but others as well have been preoccupied (nay, sidetracked) with issues to some degree inconsequential, such as health or wealth. Taglines such as “God wants you well” or “Name it/claim it” have been on the lips of thousands of believers and the subject of many thousands of sermons. Does God want Christians to be healthy and if they are not, is their faith lacking? Was Martin Luther’s faith wanting because he died of a stroke and possibly a coronary? Was John Newton spiritually weak because he lost his vision? The Apostle John had to be carried around in his old age because of his infirmities. The apostle Paul had health issues, quite possibly cataracts, as well as his “thorn in the flesh” whatever that might have been. He pleaded with God repeatedly for a healing which never came. People who God used in order to heal others later succumbed themselves to some form of illness, whether pneumonia, cancer, or heart disease. I’ve reached the conclusion based on all I’ve read and observed that God can and does heal people today, but it’s often through medicine and it is often the exception rather than the rule.

Then there is wealth. The more prominent evangelists sometimes earn (and vigorously defend) their seven-and occasionally eight-figure salary. Their own particular wealth and the wealth of the members of their churches seems to be the point of their preaching. “God wants you to be rich and prosperous!” “God wants me to buy (a) another private jet; (b) another satellite TV station; (c) a larger church” (choose one). Does God prefer Falcon jets over Gulf Stream? What a difficult decision to make. What of Christians in other lands who pray daily just for scraps of bread to eat, or that Boko Haram terrorists might release their daughters unharmed? There are likely very few jewel-bedecked ministers with expensive Rolex watches in Uganda, Tanzania or Timor. Does God love impoverished people less than prosperous one or does He favor the wealthy?

I did a cursory search through the Bible once and God seems to be much more attentive to, and concerned with the poor than the rich. Not only that, He also seems concerned with issues such as social justice.

Psalms 103:8-14 NKJV

The LORD is merciful and gracious, Slow to anger, and abounding in mercy. He will not always strive with us, Nor will He keep His anger forever. He has not dealt with us according to our sins, Nor punished us according to our iniquities. For as the heavens are high above the earth, So great is His mercy toward those who fear Him; As far as the east is from the west, So far has He removed our transgressions from us. As a father pities his children, So the LORD pities those who fear Him. For He knows our frame; He remembers that we are dust.